Recently Rauma Marine Construction announced a MoU with the Tasmanian TT-Line to build in 2022–2023 two Ro-Paxes in Finland and simultaneously reported that the RMC orderbook already had exceeded 1 billion euros in value. These two announcements well reflect the excellent growth path in the Finnish Maritime Cluster that prevailed in 2018 and 2019. The marine, shipping and port industries in the private and public sectors are the three main interdependent groups of the Finnish national maritime cluster. Since the 2008 financial crises there was a continuous growth for all these maritime segments.

Since the first maritime cluster report published in 2003 for Finland on initiative of the Finnish Maritime Association there has been continued analytic gathering of data by the Turku University Brahea Center with a “bottom up” method from the accounts of all the 3.000 enterprises working within the cluster.

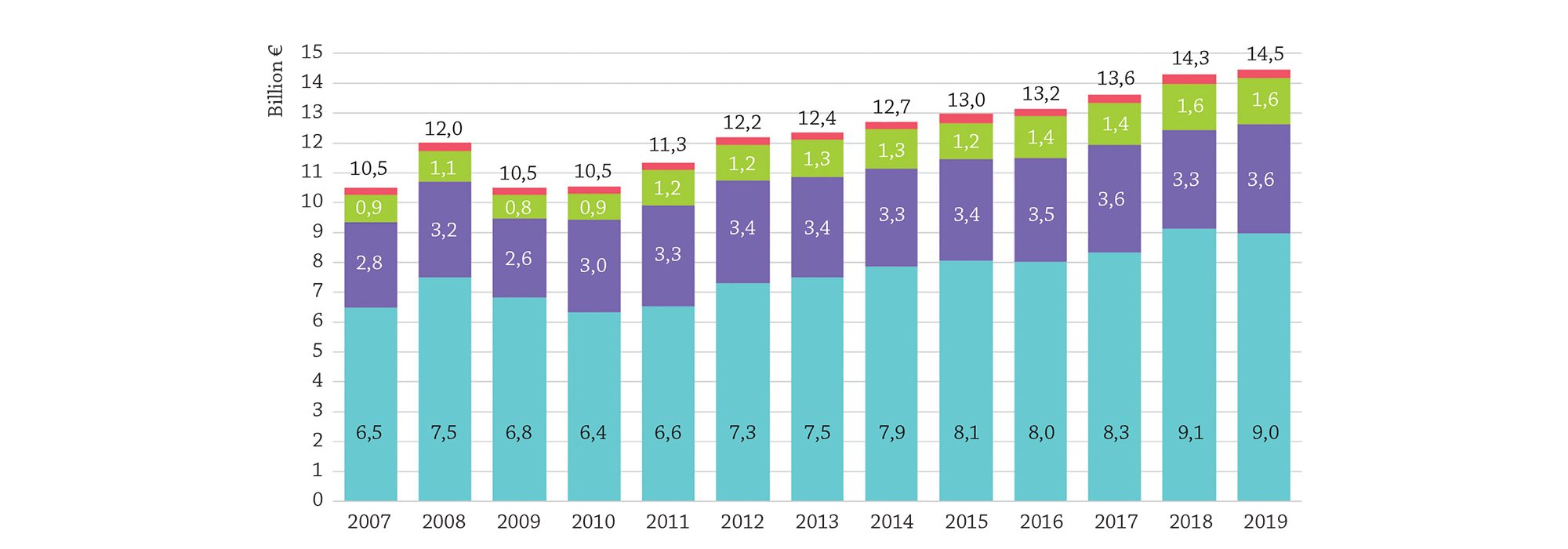

Since 2008, despite of the challenging global maritime market environment, the total turnover of Finland’s maritime cluster has grown from 10,5 billion € steadily to 14,5 billion € in 2019, from where the latest figures have been available. According to estimates this overall figure in 2020 will exceed the 15 billion € mark.

With a record order book at the shipyards extending to the year 2026 and the ship owners having 13 environmentally advanced ship newbuildings valued at one billion underway under Finnish flag, this steady growth scenario was still the case in the beginning of March.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a doldrums never experienced before. The collapse in 2008 was about 10% in the Finnish maritime cluster but the preliminary estimates today indicate something similar, or even worse. At the time of this writing all the yards have been able still to continuously operate, the dry bulk and tanker shipping is continuing, with significant downfall in the summer, but are now recovering, but the regular ferry services are hit hardest. Some of the lines still operate only as rolling cargo carriers with the financial support from the National Emergency Supply Agency and Transport Safety Agency, as all passenger traffic over the closed borders was for several months generally prohibited and today the on-board entertainment activities are restricted and some routes totally closed down. The yards’ delivery times have been put forward and e.g. the MoU mentioned above has so far not been confirmed as a firm contract.

From continued success and growth into unknown

About 3,000 companies operate in the Finnish maritime cluster and more than 1,800 limited liability companies had submitted their 2019 accounts to the authorities. As a summary, the total maritime cluster turnover increased to 14,5 billion euros while the directly employed personnel was 48,500.

The total turnover of Finnish marine industry (shipyard, equipment manufacturers, services) and related services remained close to the EUR 9.0 billion of the previous year. In 2019, the industry employed a total of 29,600 (30,600) people in their marine-related businesses. It is important to note that these “bottom-up” figures, collected directly from the accounts of the marine industry, differ considerably from the figures of the EU Commission’s cluster data, which is collected from Eurostat. According to the EU Commission shipbuilding’s turnover in Finland in 2018 was EUR 1,4 billion, but equipment and outfits only 300 million, whereas the reality is for them more than 7,3 billion EUR. Unfortunately Eurostat is not counting at all the equipment industry and therefore only assumptions are made.

The dominant part of Finland’s marine industry is other than shipbuilding, mainly equipment manufacturing and services.

The factual marine industry figures reflected especially the good market situation for cruise ship construction, which was forecasted already a year earlier by Mr. Tapio Karvonen at the University of Turku, Brahea Center, who has led the updating study of the economic indicators. The combined net sales of the largest shipyards increased in 2018 by almost 18% despite the continued weak market situation in the offshore business. Mr. Karvonen expects that in the 2020 figures the positive development of the strong orderbook will continue in shipbuilding, as the turnover growth will begin to be seen more in the subcontracting network companies.

Conclusions From The Cluster Study

› The Finnish maritime cluster is made up of companies that combine marine expertise and mutual interaction. The cluster’s versatility is not easy to see, for example, in media reporting on the industries.

› The marine cluster should be considered as a versatile market-specific value network. The versatility of the cluster’s demand structure means that the economic success of the cluster is not homogeneous, but the fluctuations of the global market cycles affect the cluster parts in different ways and at different times.

› The activities of cluster companies are strongly international, and fostering international connections is the lifeblood of the cluster.

› The share and importance of foreign ownership in Finnish maritime cluster companies has increased. Although foreign ownership is estimated to be largely positive in terms of the development of the industry, retaining of a fleet of national ownerships and flying of Finnish flag must be ensured to maintain security of supply. It is therefore important to preserve the overall competitive national conditions now available in shipping.

› The influence of the 2008 financial crisis on the Finnish maritime cluster was dramatic. However, the aggregate turnover of the cluster companies have been steadily increasing since 2010 and growth is expected to continue for at least the next few years. The business outlook varies by main categories due to cyclicality, which is a significant feature of the industry. Especially in the

construction of cruise ships, the outlook for 2020 and beyond is bright, while the oil and gas and global freight markets are currently facing challenges.

› The strength of the Finnish maritime cluster can be seen in the diverse markets that balance each other.

› There are already good examples of new emerging businesses in the blue bioeconomy and renewable energy developments

› Renewal of companies takes place through a wide range of innovation activities. We must therefore ensure that Finland has an operating environment that enables the launching and piloting of new ideas, technologies and operating models in Finland.

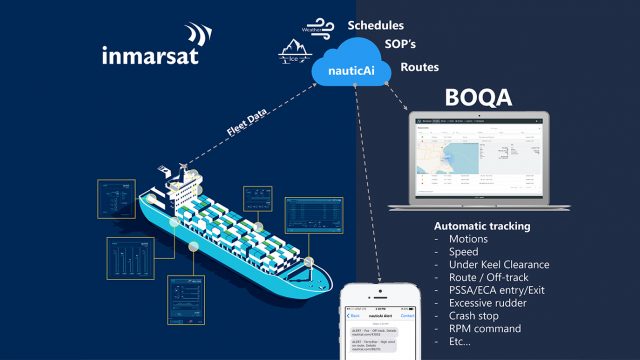

› New enterprises in the maritime cluster often arise to benefit from existing technologies or ideas that are still unknown from other fields. At present, companies involved in large-scale digitization processes, for example, combine technologies developed in other sectors with traditional maritime cluster activities, possibly revolutionizing industry practices.

› Shipping is an industry that operates strategically independently, building a growth-generating business. So shipping is not just a continuation of the transport network serving the needs of industry, but an independent industry that has to have its own national business policy.

› The competition between ports is intensifying as total traffic volumes do not grow and logistically it would be cost-efficient to combine and concentrate export and import of general cargo. The Finnish transport system needs an overall visionary reform.

› The global field of action is unpredictable, so marine clusters must ensure their ability to survive by preparing for many future options. A strong knowledge base must be guar- anteed by quality education and research. In particular, new maritime education and maritime training resources should be created.

› For many, the long-term future of the marine cluster seems to be quite bright and includes many opportunities for development for both large and small operators.

› In order to support international operations, not only cluster actors, but also administration, politicians and, for example, delegations from the public and private sectors, should strive to strengthen the brand of a highquality and diverse Finnish maritime cluster.

The net sales of the shipping and other shipping-related operations was EUR 3.6 billion. The favorable development of the freight market in 2019 is the most important factor. On the passenger side, the change has been much smaller.

In port operations the volume of foreign trade sea transport increased and the volume stabilized around EUR 1,6 billion and number of personnel somewhat lower, 6,300 (6,600).

From silos to active cluster cooperation

Two major cluster studies were conducted in Finland in the years 2003 and 2008. During the shipbuilding market collapse in 2013 Finland was lacking proper economic indicators on the branches and on the Finnish Maritime Association’s initiative funding was made available for a new, updated cluster study. One of the conclusions of the CEO interviews in the most recent 2015 cluster study was the low level of interaction between the various segments in the cluster.

In addition to the conclusion of the economic importance of the maritime cluster for the nation, the Government of Finland launched a number of special programs to enhance the maritime clustering.

These included establishing of a specific maritime technology promotion program valued up to 100 million EUR between 2014 to 2017 as well as granting support to a project for enhancing the clustering from 2016 to 2020. See finnishmaritimecluster.fi. In October 2016, the Prime Minister’s Office finally appointed a steering group on the Baltic Sea and maritime policy, with representatives from different ministries, to prepare an update of the Government Report on the Baltic Sea and to develop and coordinate, for the first time, the

national maritime policy.

At the first stage of the work, the steering group prepared Finland’s Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region and in the second stage the guidelines for Finland’s maritime policy. The guidelines were prepared in close cooperation with various stakeholders. The Government adopted the maritime policy in January 2019, as “Guidelines for Finland’s Maritime policy”.

According to the vision for the policy, Finland has global influence and produces solutions to ensure that the use of marine natural resources is sustainable, the status of the marine environment is good, and the impacts of climate change do not exceed the carrying capacity of the oceans. The guidelines determine the focus areas of Finland’s maritime policy, extending all the way to the oceans.

While the guidelines were in the planning, on the basis of the cluster study conclusions, a special project “Finnish Maritime Cluster” was established. This book is an example of the results of this further clustering, achieved in the best cooperation of the various cluster segments. The work of the cluster project has been very active and many international events have been set up, especially on the digitalization and autonomous ship development sector.

Last September the national steering group for the maritime policy funds under the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF) was reappointed and the composition revised. Its term has been extended until June 2022. The steering group monitors the implementation of the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund’s operational plans and projects derived from it. The steering group is also participating in the preparation and implementation of the EMFF’s 2021–2027 funding as concerns maritime policy.

The maritime cluster study itself was conducted by the University of Turku, Brahea Center jointly with the university’s Business School. The yearly work on updating the cluster indicators has also been carried out as part of the Maritime Information Portal project funded as mentioned above by the Finnish Government jointly with the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF), as part of preparing for an open data portal for Finland’s all maritime activities. This comprehensive public portal www.MaritimeFinland.fi was launched in the beginning of April, 2020.

TEXT MIKKO NIINI

PHOTO TIMO PORTHAN